So What?!

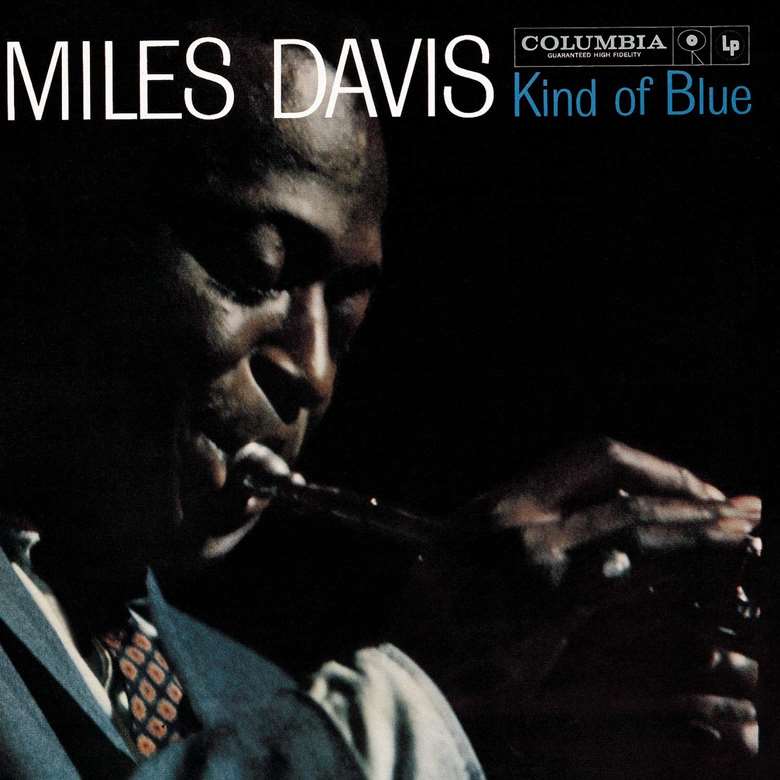

When I first bought Kind of Blue, I didn’t realize how special it was. I was just trying to build my jazz music collection, and I’d heard that Miles Davis was someone to be familiar with. It became one of my favorite albums, and I quickly wore out the cassette tape. At the time I couldn’t have explained why the songs were so compelling. All I knew is that I couldn’t stop listening. Now, decades later, it all makes sense.

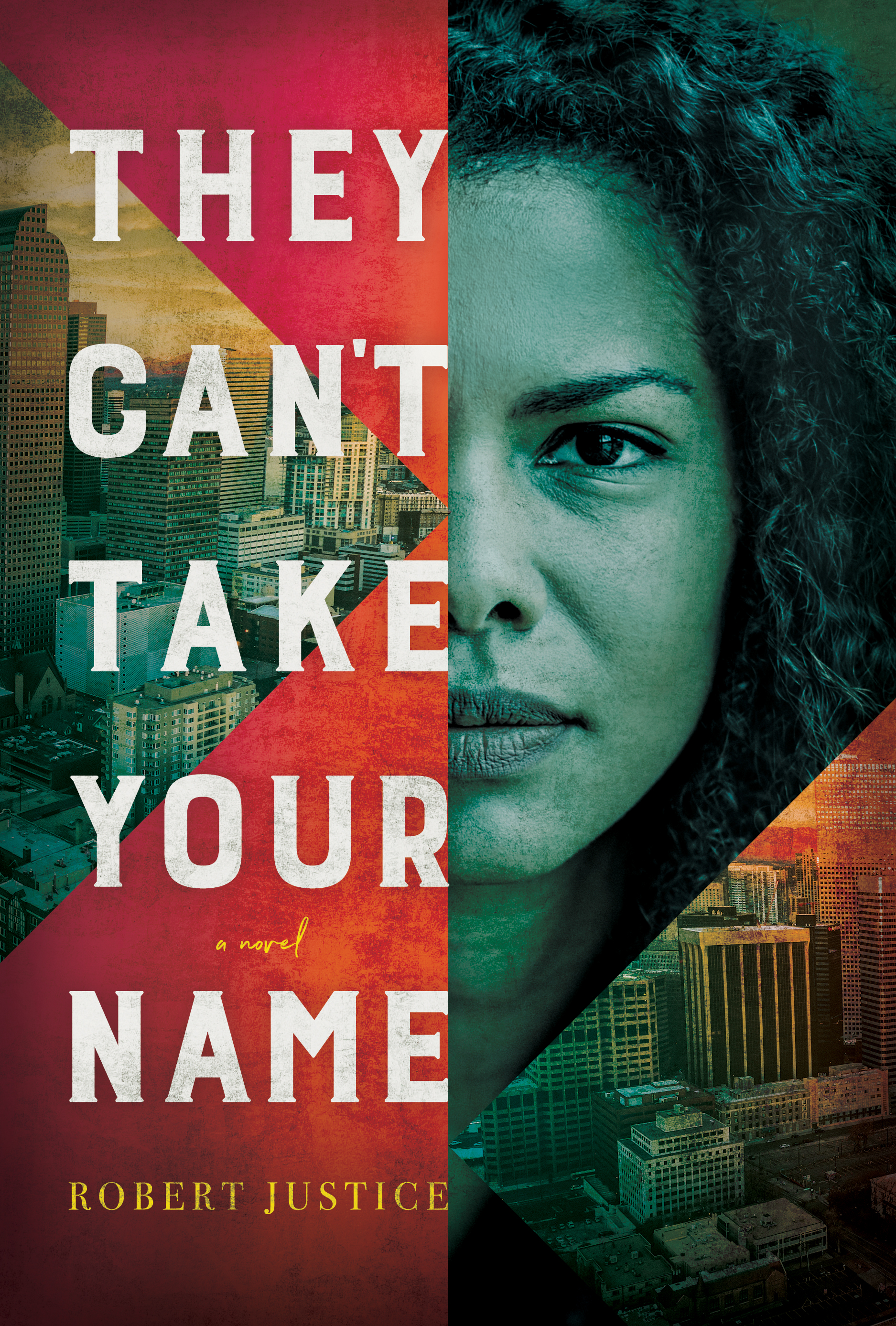

When I first bought Kind of Blue, I didn’t realize how special it was. I was just trying to build my jazz music collection, and I’d heard that Miles Davis was someone to be familiar with. It became one of my favorite albums, and I quickly wore out the cassette tape. At the time I couldn’t have explained why the songs were so compelling. All I knew is that I couldn’t stop listening. Now, decades later, it all makes sense.Kind of Blue was recorded by Miles Davis in 1959, and it’s one of the best-selling jazz albums ever. It was named one of the ten best albums in any category during end-of-the-century polls. Kind of Blue is the only jazz album to achieve double platinum status, and it continues to sell strong today. With trumpet in hand, Miles called together an ensemble comprised of tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, alto saxophonist Cannon-ball Adderley, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Jimmy Cobb. This group of practiced musicians combined to produce what some have called the most influential jazz album of all time.

Many believe that jazz history divides into two segments — “before Kind of Blue and after Kind of Blue.”

"So What” is the subtle yet unforgettable first song on Kind of Blue. On the back cover of the album, there isn’t a question mark after the title “So What.” This wasn’t a typographical error. It looks like it should be a query, but it’s not. “So What” is a declaration. Eric Nisenson observes, “Kind of Blue was created . . . because the most important jazzmen in the modern scene desperately wanted to change the way they played their music. This need was not purely musical; it had more than a little to do with the changes then going on in American society.”

“So What” was a statement: The old is gone, the new has come!

Kind of Blue marked the end of an era for jazz music and the beginning of something fresh. It pre-called what was about to happen in American society. To grasp this, we need to remember what life in America was like in the years leading up to 1959. The war was over, the invention of suburbia was underway, and, for most, the pursuit of the American Dream was back on track.

Yet in the African-American community, the 1950s were a decade of tension. After ninety years of blacks’ not being slaves and yet not being citizens either, something had to give. The dehumanization of separate water fountains, segregated schools, lynchings in the South, massive nihilism in the urban North, and absence of voting rights gave rise to discontent. As Fannie Lou Hamer would say, sometimes you’re just “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

At the same time, jazz music had an inferiority complex. It was always compared to classical music and never felt as legitimate as its European counterpart. Jazz music pre-1959 too often sought to conform to classical standards, complete with big bands modeled after orchestras. Not satisfied with this, many jazz musicians were experimenting with new ways of playing in jazz, as they pondered the question, “What if classical music was ‘a’ standard but not ‘the’ standard?”

Before 1959, which is pre – Kind of Blue, conformity was the way of seeking acceptance into the melting pot of the American Dream. This was seen as the key to success for many African-Americans in general and jazz musicians in particular. Larger society thought that jazz music was simply the product of an innate sense for rhythm of African-Americans and that it was nowhere near as sophisticated as classical music. Black musicians sought to counteract this perception by increasing the complexity of their music in an attempt to demonstrate that it was a music of intelligence. All of this created a visceral uneasiness. With black soldiers fighting a war against hate and fascism in Europe, they found it difficult to return to a country still having to prove themselves.

Around the time of the recording and release of Kind of Blue, Miles Davis used to do something that some found offensive: he would play with his back to the audience. Unable to use the same restrooms or entrances as his white patrons, Miles wanted to make a statement as he stood on stage. Some saw this as an act of arrogance. Others saw it and began to hope. After all, if a mere musician would dare turn his back in protest to society, then what else was possible — common drinking fountains, same schools, voting rights, no more lynchings?

There was another reason why he played with his back to his listeners. Miles once said that by turning and facing the band, he could listen better, read their cues, and ultimately produce a better musical experience for the audience. In spite of his disdain for a society that contained so much blatant inequality, he sought to give a gift.

Musically, Miles Davis decided to blaze a new trail with a new set of standards. After seeing an African dance troupe and listening with amazement to the beats of the drummers, he set aside European chord progressions as the best way to play jazz and went with what is called a modal approach, based on scales. And in a two-day recording session, Kind of Blue emerged. It became “a watershed in the history of jazz, a signpost pointing to the tumultuous changes that would dominate this music and society itself in the decade ahead.

Indeed, something was afoot. In 1954, racial segregation of schools was ruled unconstitutional. In 1955, Rosa Parks decided to stay seated on a city bus. In 1959, Miles Davis recorded Kind of Blue. Four years later, Martin Luther King Jr. called America to live out the true meaning of our creed.

Kind of Blue anticipated and participated and sensed the shift of the wind.

Kind of Blue calls us to no longer be satisfied with a series of static propositions or the status quo; to sense current realities and anticipate what will happen when the new arrives; to turn our back on injustice only to include and create something beautiful for everyone.