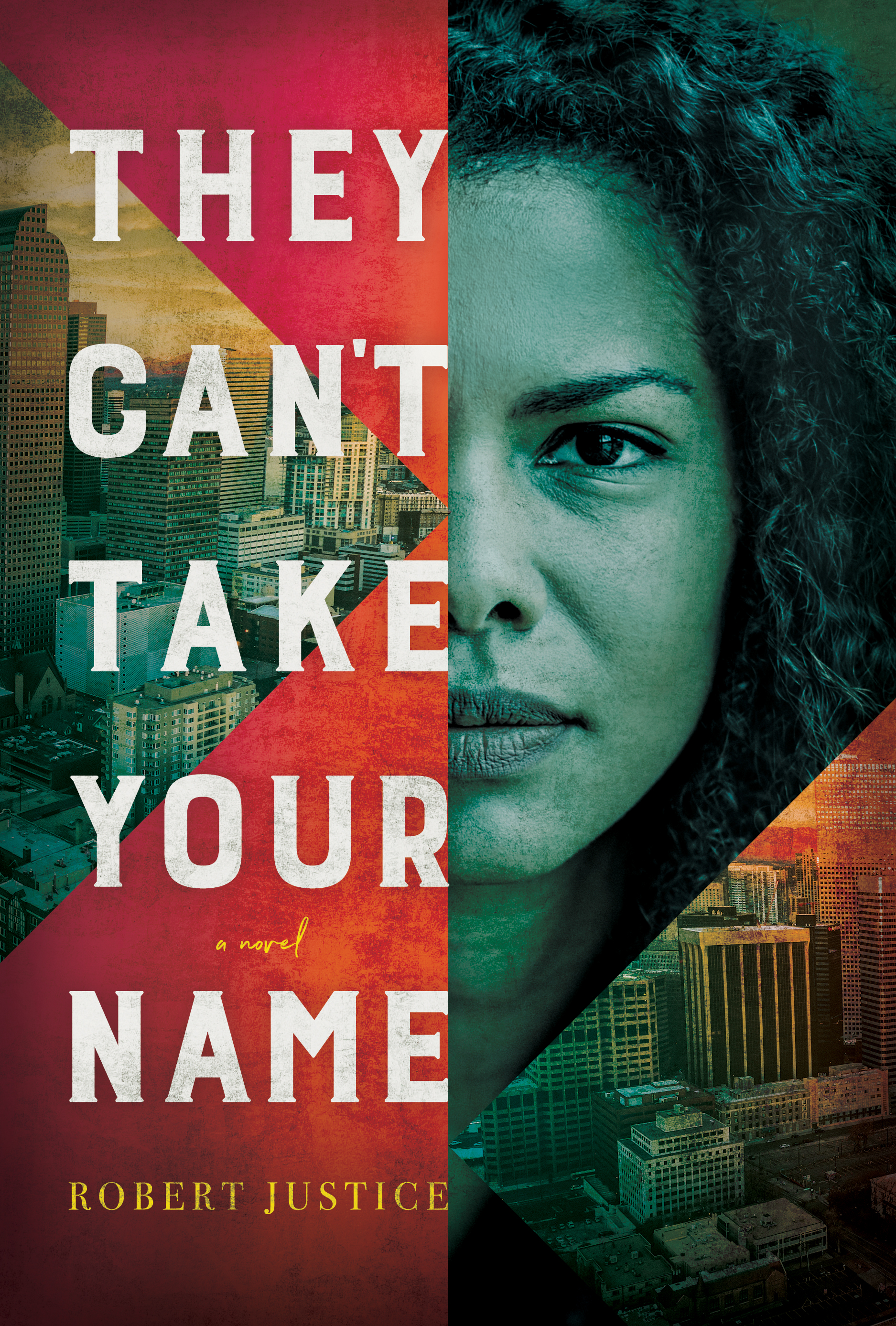

Author's Note—THEY CAN'T TAKE YOUR NAME

If you listened to audio version of THEY CAN'T TAKE YOUR NAME then you missed my Author's Note included in the hardcover and eBook versions.

Thought I'd make it availabe here so you might also read about...

- Why I wrote the book

- The true to life elements included in the book

- Writing Wrongful Convictions

- Read a Book, Right a Wrong

- Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, and All That Jazz

- Acknowledgments and Thank-Yous

Enjoy!

(Note: My Author's Note contains spoilers!)

AUTHOR’S NOTE

My wife’s cancer forced me to face my greatest fear: life without her.

While Barbara was in treatment, people would often pull me aside to ask how I was doing. In my honest moments, I responded, “It doesn’t matter,” for I didn’t feel I had the luxury of answering that question. I was trying to be supportive of my wife, present for our children, and on schedule with a publishing deadline—all while keeping up with work day after day. If I wasn’t doing well, there was nothing I could do about it.

After three surgeries and twenty radiation treatments, thankfully and by God’s grace, my wife was OK . . . but I was not.

There was a truth that her sickness forced me to face: in all likelihood, one of us is going to die before the other, leaving the survivor to deal with the pain—I could be the one to live longer. This truth became a suffocating visceral feeling that took up residence in my chest. Someday, something could take my beloved of more than two decades, leaving me to face a pain matched only by my love for her.

They Can’t Take Your Name was my way of facing that reality, and then it turned into a crime novel!

Separating Fact From Fiction

I’ve lived my whole life in the Mile High City, and—like any author—I write what I know. Historically, Denver’s black community found solace in a neighborhood known as Five Points where the historic Rossonian jazz club (The Roz) has sat empty for decades. For years, before gentrification set in, Five Points was a place that I would go to find respite from life outside our historic home. During these times, I’d often dream of restoring and reopening the legendary jazz club.

The Mother’s Day Massacre was actually the Father’s Day Bank Massacre that happened June 16, 1991, in downtown Denver in what was the United Bank building—what locals call “the cash register building.” I borrowed the basic details from this unsolved crime in our city, including the fact that an former police officer was found not guilty in the same way described in the book. The crime and trial took place when I was in my early twenties, and I remember thinking that a black man would have been convicted under the same circumstances. This tragedy provided the basic framework for Langston’s wrongful conviction.

In 2017, the state of Arkansas did, in fact, announce a plan to execute eight men over the course of eleven days. Such a mass execution season was unprecedented in the United States, and—as one would hope—many people rose in opposition. One of the reasons given for the rush was that the state’s supply of the drugs used for lethal injections (“the death cocktail”) had already or were about to expire.

Writing Wrongful Convictions

Unfortunately, wrongful convictions are all too real in our justice system. As I write, almost 2,500 men and women have been exonerated, totaling more than 21,000 years lost. Conservative estimates are that only 1–2 percent of all convictions are of innocent people. That’s an impressive success rate, and it can be comforting to think that our criminal justice system incarcerates the correct person 98–99 percent of the time. However, this is not good news if you are among the 1–2 percent. Think about what that means in actual numbers. There are approximately 2.5 million people incarcerated in the United States. Conservatively, then, there are thousands of innocent people doing time for crimes they did not commit.

Have we executed an innocent person in the United States? I am not aware of a verifiable case of a wrongful execution. However, with the history of vigilante justice and lynchings in the United States and the sheer numbers of wrongful convictions in the modern era, it’s reasonable to suspect it has happened. Having Langston, an innocent, meet his end unjustly was my way of trying to help us come to grips with this reality.

Our criminal justice system in the United States is broken. Reform—transformation—is needed to address mass incarceration and the fact that the largest mental health facilities in this country can be found in our jails and prisons.

What can you and I do about wrongful convictions? First, we should understand the well-documented anatomy of a wrongful conviction. We know the root causes that lead to convicting the innocent:

- False and contaminated confessions (innocent people pleading guilty)

- Eyewitness misidentifications (especially cross-racial misidentification)

- Flawed forensics and junk science (false or misleading experts)

- Jailhouse informants (trial by liar)

- Plea deals

- Incompetent counsel and/or inept lawyering

- Unscrupulous law enforcement professionals

- Corrupt evidence

- Shoddy investigative practices

- Lack of DNA testing

- Racial bias

Some of these causes must be addressed at the level of those in charge—police, district attorneys, and judges. But because our system is ultimately a very human system in which we are judged by a jury of our peers, we as citizens must learn to spot these root causes when we are called upon to cast judgment on someone’s life.

Only a few of these root causes made their way into the story line of They Can’t Take Your Name, which means you’ll be seeing more of Eli and Liza as they fight what I believe to be the greatest injustice in our justice system—wrongful convictions.

You’ve already made a difference just by purchasing this book (and future books in this series). I have donated a share of my advance and am committed to giving a portion of all future proceeds to my favorite innocence project, The Korey Wise Innocence Project at the University of Colorado. The average cost to free an innocent person is enormous, and my hope is that this series of books will raise enough money that we might actually be able to say that together we had a part in somebody’s freedom.

Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, and All That Jazz

Jazz is more than music; it’s a way of seeing and interacting with the history of America. This is why I love the work of Langston Hughes and Ralph Ellison. When Hughes wrote his poem “Harlem: A Dream Deferred,” he was doing jazz. He was not the first of the jazz poets, but he is definitely the most notable. These poets began by including references to music and musicians in their prose. Then they quickly embarked on applying what they saw the musicians doing on the stage and translated it into their verse. Making use of the elements of jazz, they gave birth to a new way of doing poetry—poetry in jazz. Read Langston Hughes and you find syncopation, improvisation, and call-and-response, especially as he interacts with the great American novelist Ralph Ellison.

Ellison was a trumpeter and lifelong lover of jazz. He not only asserted that all of American life is “jazz shaped”; he sought to demonstrate it when he wrote the great American novel Invisible Man. Ellison, a longtime jazz critic, moved from writing about jazz to writing in jazz. This is most evident in Invisible Man, in which he responds to the poetic call of his friend Langston: What happens to a dream deferred?

He hints at this in the prologue to his novel when the main character seeks to light his underground darkness by illuminating it with 1,369 light bulbs. The number is a coded tribute to the year 1936—the year Ellison moved to New York City during the Harlem Renaissance and met Hughes.

Ellison’s work is a jazzlike response to Hughes’s call: What happens to the American Dream when it is deferred for a group of people? (The answer, by the end of Invisible Man, is a resounding “It explodes!”)

They Can’t Take Your Name is my feeble attempt to join the Hughes-Ellison Ensemble. Eli’s underground abode is a nod to Ellison’s Invisible Man, and naming our innocent man Langston and including Hughes’s poetry throughout this novel was my way of adding my voice to the conversation that they began about race in America.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND THANK-YOUS

To my Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name.

To my children, Selah, Kia, Gabriel, James, Mihret, and Temesgen—because of you, my cup overflows.

To Andrew—you’ve always been more than an agent, a true friend indeed.

To all my beta readers (Barbara, Jeff, David, Janella, Ten, Chris, Heather, Mihret)—your feedback was invaluable.

To Jevon Bolden and Shana Murph—your early editorial advice was pure gold.

To Progress Coworking—Joe and Biff, thank you for your kindness and generosity.

To the team at Crooked Lane Books—Thank you for all you did, seen and unseen, to bring this book into existence. Terri Bischoff, your editorial skills and encouragement along the way were invaluable. Thank you for believing in this book.

To the Crime Writers of Color group and all the listeners to the Crime Writers of Color podcast—I’m so grateful for who we are and what we represent.

And finally, to my bride, Barbara Anntoinette—you will always be my inspiration.

It has been said “Write something that may change your life . . . and when you’re done writing the story, no matter what else happens, you’ve changed your life.” I hope that those who read this novel are—at a bare minimum—entertained and perhaps enlightened in some way. In my most grandiose moments I dream of the end of the death penalty, for as Bryan Stevenson has so eloquently written, “The question is not do people deserve to die for the crimes they commit but rather do we deserve to kill.” With our track record of arresting and convicting innocent people, we have long forfeited any right we had to take another’s life. All of that said, regardless of the actual difference this book will make in the broader world, I’m certain that writing They Can’t Take Your Name did, in fact, change my life, and for that I’m grateful.

Oh yeah, Denver is also home to two rare blooming corpse flowers named Stinky and Little Stinker.

Robert Justice

Micah 6:8